海外之声丨货币政策与财政政策如何保护稳定与信任

导读

根据货币政策与财政政策的长期发展趋势以及政策的累积效应,提出“稳定区域”的概念,在“稳定区域”的范围内,两大政策之间的紧张关系保持在可控范围内。在此概念下有三条结论:首先,早在疫情之前两大政策就已经徘徊在“稳定区域”的边缘。其次,长期政府债务的趋势是最大的威胁。最后,要保持在“稳定区域”的范围内,就必须进行战略、制度以及思维的调整。

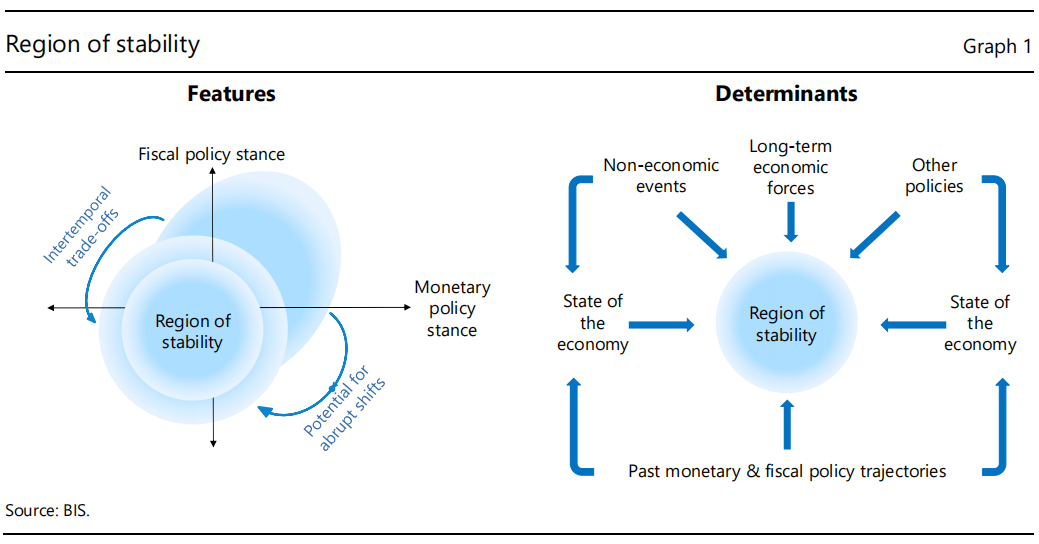

货币政策和财政政策对经济有重大的影响,因此也承担着巨大的责任。“稳定区域”规定了政策权利行使的合理范围,而区域的规模和形态取决于经济状况,尤其是金融业的状况。有两大重点特征需要注意:其一,经济状况和两大政策的双向反馈有助于短期和长期的政策权衡;其二,“稳定区域”的范围既不稳定也不确定,受到市场信心等多重因素影响。这两大特点加上疫情的爆发,使得经济趋于不稳定,甚至出现混乱。

从历史长河来看,出现问题的根源是政策对经济扩张的限制。自20世纪80年代中期之后,通胀稳定保持在较低水平,掩盖了经济扩张限制的问题,导致经济增长越来越依赖于公共和私人债务积累。而随着货币政策正常化,最大的风险是政府债务的不可持续性,它给物价和金融稳定带来了严重风险。

基于上述分析,当前财政政策、货币政策的要务是保持经济在“稳定区域”内运行。从财政政策来看,必须确保债务的可持续性;从货币政策来看,必须确保物价和金融稳定。除此以外,还可以采用微观和宏观审慎政策以及结构性政策。

总而言之,我们必须更敏锐地认识到需求管理政策的局限性。“稳定区域”的概念虽然很难践行,但可以促进观念的转变,使其成为观察世界和指导政策的窗户,保障社会民众对国家及决策的信任。

作者丨Claudio Boris(国际清算银行货币经济部主任)

Monetary and fiscal policy: safeguarding stability and

trust

Speech by Claudio Borio

Head of the Monetary and Economic Department, Bank for International Settlements

on the occasion of the Bank’s Annual General Meeting in Basel

25 June 2023

Some things never change. One of them is monetary and fiscal policy’s perennial search for coherence and stability. The two policies are simply too closely intertwined. And their influence on the economy too powerful.

Over the past year, we have seen the latest example of tensions. Monetary policy has been restraining aggregate demand to quench inflation; fiscal policy has been boosting it to shield activity from higher commodity prices. And higher interest rates have widened fiscal deficits.

But the challenges go way beyond the short-term policy mix. They have to do with long-term trajectories and their cumulative impact. This is the focus of this year’s Annual Economic Report.

To shed light on those challenges, we put forward the notion of the region of stability. The region maps constellations of the two policies that foster sustainable macroeconomic and financial stability, and that keep tensions between the policies manageable.

We reach three conclusions.

First, even before the Covid crisis struck, the two policies had been approaching the boundaries of the region. Hence the recent unique combination of high inflation and widespread financial vulnerabilities.

Second, looking ahead, longer-term government debt trajectories pose the biggest threat. They have been relentlessly narrowing the region of stability and will continue to do so.

Finally, operating firmly within the region calls for adjustments to strategies, institutions and, above all, mindsets. The objective is to dispel a kind of “growth illusion” – a de facto excessive reliance on monetary and fiscal policy to drive growth.

Let me say a few words about the nexus between monetary and fiscal policy as well as the region of stability, the journey to the boundaries, the risks ahead and the policy implications.

The policy nexus and the region of stability

Monetary and fiscal policy are inevitably tied closely together. They give the state privileged access to resources, through the issuance of money and the power to tax, respectively. They back each other up: monetary policy can avoid the government’s technical default; the power to tax ultimately backs the value of money. They operate through intertwined balance sheets – those of the central bank and the government. Their transmission mechanisms overlap, notably through financial conditions. And they have a major impact on the economy.

With this great power comes great responsibility. The region of stability, illustrated in Graph 1, delineates the range of policy settings that are consistent with the proper exercise of that power. Drifting outside the region generates large economic costs, in the form of slumps, high inflation and financial instability.

The region’s location, size and shape depend on the state of the economy, not least that of the financial sector. In turn, the state of the economy depends on two sets of factors. One includes factors other than monetary and fiscal policy. Think, for instance, of non-economic events, eg a pandemic or a war, of powerful long-term economic tectonic forces, eg globalisation and financial liberalisation, or of other policies, notably, prudential policy. The other set comprises monetary and fiscal policies themselves – in particular, their past trajectory and their cumulative impact on the current state of the economy. Think, for instance, of the impact of past deficits on government debt or of long periods of very low interest rates on financial vulnerabilities.

Two important features stand out.

First, the two-way feedback between the state of the economy, on the one hand, and monetary and fiscal policy, on the other, opens the door to intertemporal trade-offs. Policy settings that may appear reasonable, indeed compelling, in the near term may cause problems down the road.

Second, the contours of the region are fluid and can be hard to discern in real time. They may become clearly visible only ex post. And instability may emerge abruptly, as confidence evaporates.

The journey so far

These two features figure prominently in the journey that has taken the two policies to the boundaries most recently.

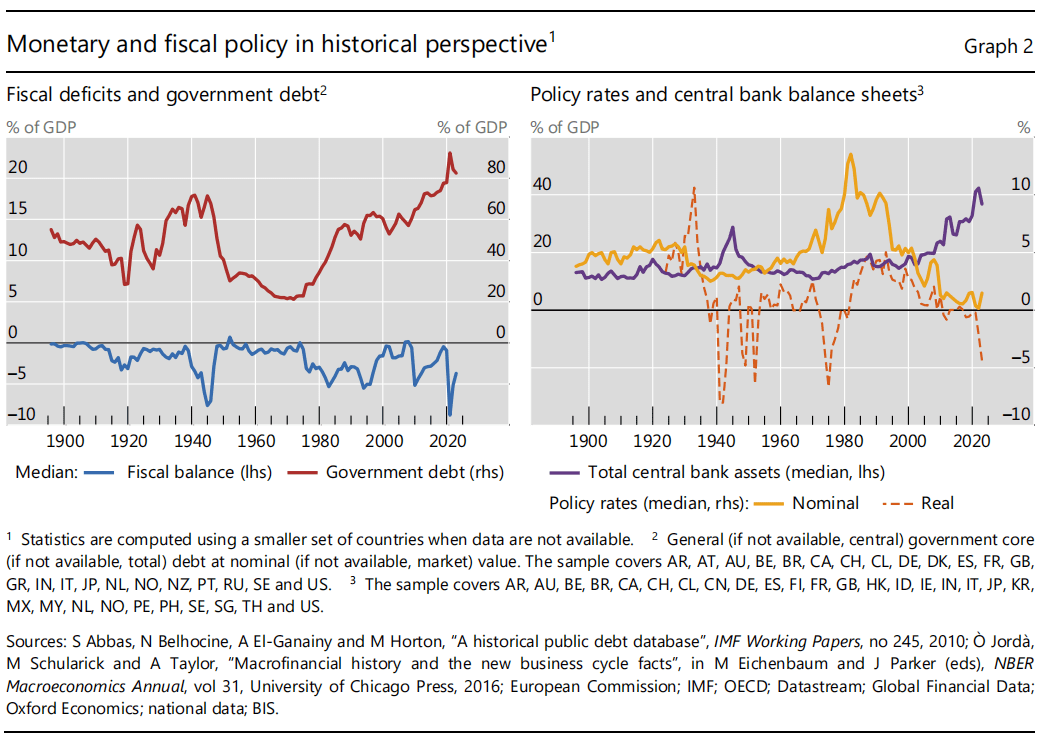

Even before the Covid crisis, the two policies were approaching the boundaries (Graph 2). Globally, after a long string of deficits, government debt in relation to GDP had climbed to historical peaks (left-hand panel). Interest rates in nominal terms had fallen to historical troughs, while, in inflation-adjusted (real) terms, they had been negative in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC). And central bank balance sheets had reached wartime peaks. Ostensibly, policy buffers and safety margins had become uncomfortably small, leaving the economy highly exposed and vulnerable.

Policies did manage to ease aggressively once again as the Covid crisis struck, but at the cost of further flirting with the boundaries and laying the ground for the recent economic dislocations.

Looking at the longer journey, back to the 1970s, this was not the first time that the boundaries were tested or breached. All such episodes shared one feature: policies underestimated the constraints on economic expansions.

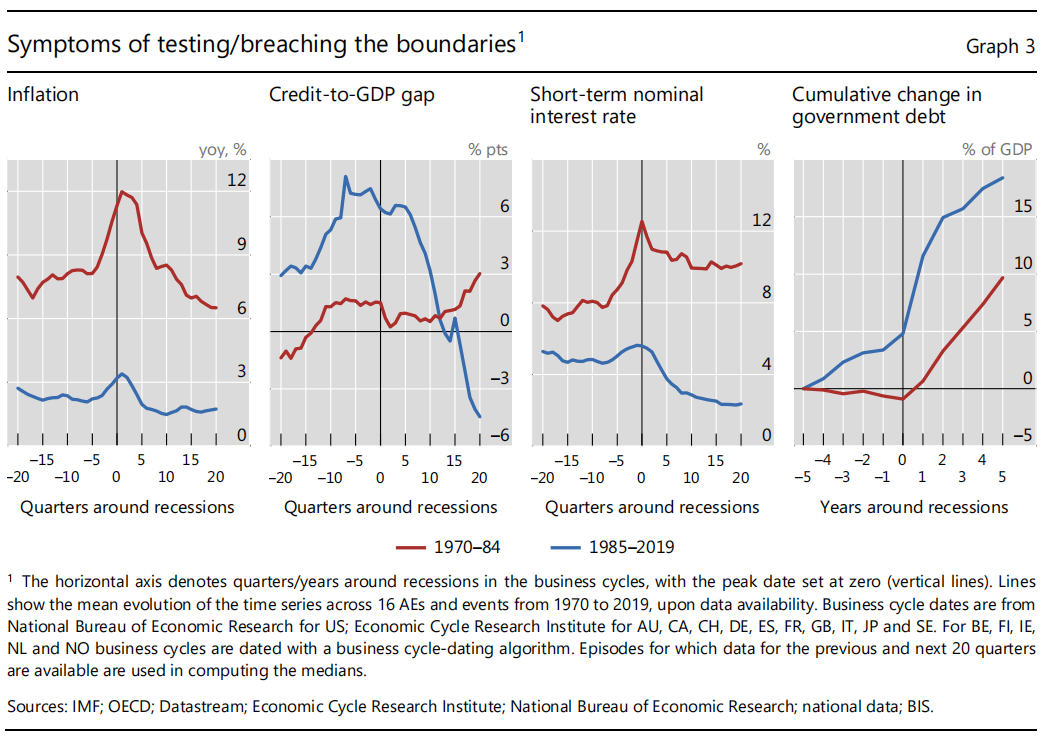

That said, the symptoms evolved over time, along with the changing nature of the business cycle and the signals of impending recessions (Graph 3). Until the mid-1980s (red lines), at least in advanced economies (AEs), the signal was rising inflation (first panel). Think of the Great Inflation of the 1970s. Thereafter, until the Covid crisis, it was the build-up of financial imbalances (second panel, blue line), here denoted by the deviation of the credit-to-GDP ratio from a slow-moving trend. Think of the GFC as the most spectacular example.

This helps explain the gradual loss in policy buffers following the mid- 1980s: policies became less systematically countercyclical. Monetary policy (third panel, blue line) had little reason to tighten during expansions, as inflation remained subdued, thereby accommodating the build-up of financial imbalances; but it eased strongly and persistently to fight the recessions, now at times exacerbated by banking crises. These financial recessions, in turn, drove large holes in the fiscal accounts (fourth panel, blue line), that were not replenished during subsequent upswings.

In the background, powerful long-term tectonic forces were also shaping the journey. Financial liberalisation amplified financial cycles. And the globalisation of the real economy helped central banks hardwire low inflation.

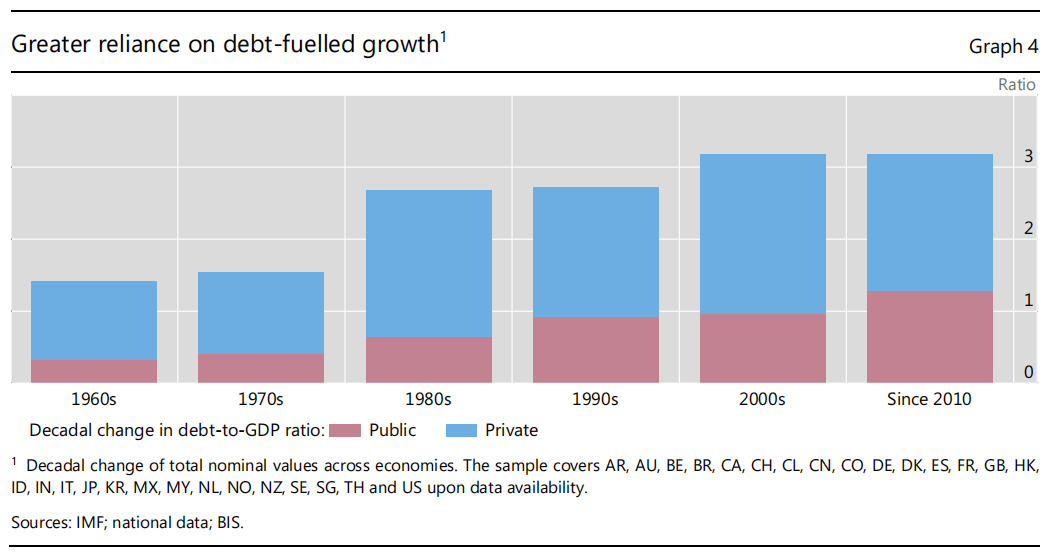

In a nutshell, after the mid- 1980s, low and stable inflation masked the constraints on economic expansions, encouraging policymakers to test them. Partly as a result, growth became increasingly reliant on debt accumulation, both public and private (Graph 4).

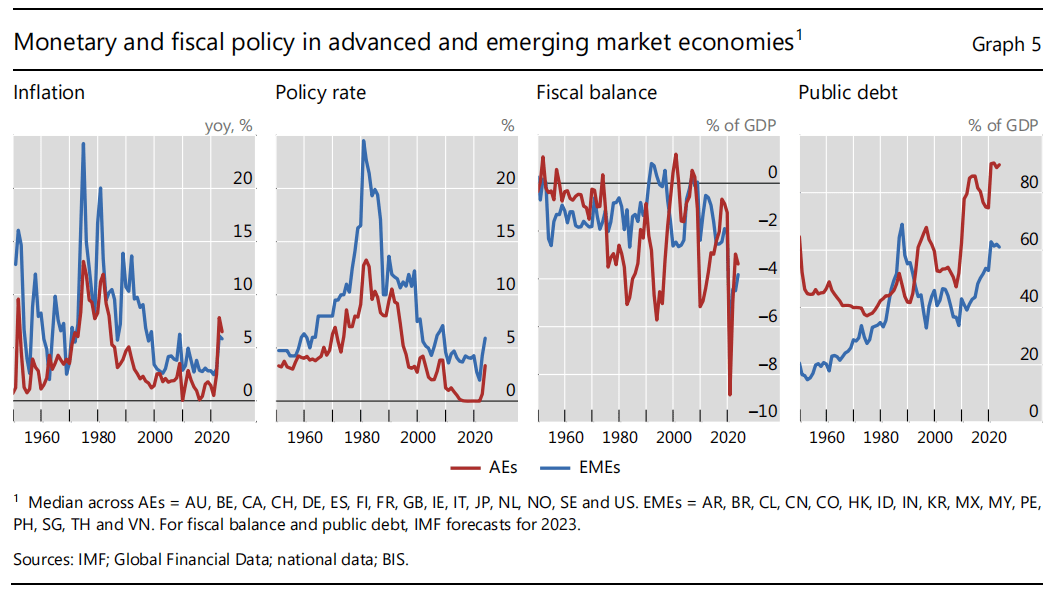

The journey in emerging market economies (EMEs) was similar in significant respects. After all, the same long-term forces were at play. Hence, the similar evolution of key indicators (Graph 5) - inflation, the policy rate, the fiscal balance and public debt.

However, regional and timing differences aside, the journey differed in one critical respect: these countries have been much more sensitive to global financial conditions, notably to monetary conditions in AEs, especially those in US dollars – the dominant international currency. Thus, the exchange rate has also played a more salient role.

The long journey explains why, today, we are seeing a unique combination of previous symptoms. In part because of the policy response to Covid, inflation has surged. In part because of the long phase of very low interest rates, vulnerabilities have built up and financial stress has broken out. This makes the current situation particularly challenging.

The journey ahead

What about the risks along the journey ahead?

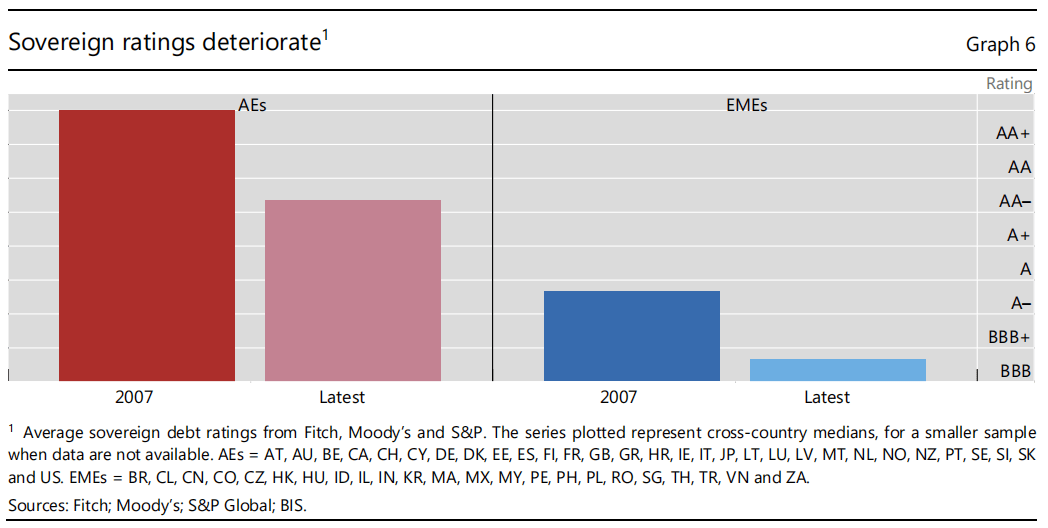

As monetary policy normalises, the biggest risk is the unsustainability of government debt trajectories – a factor which has already started weighing on credit ratings for both AEs and EMEs (Graph 6).

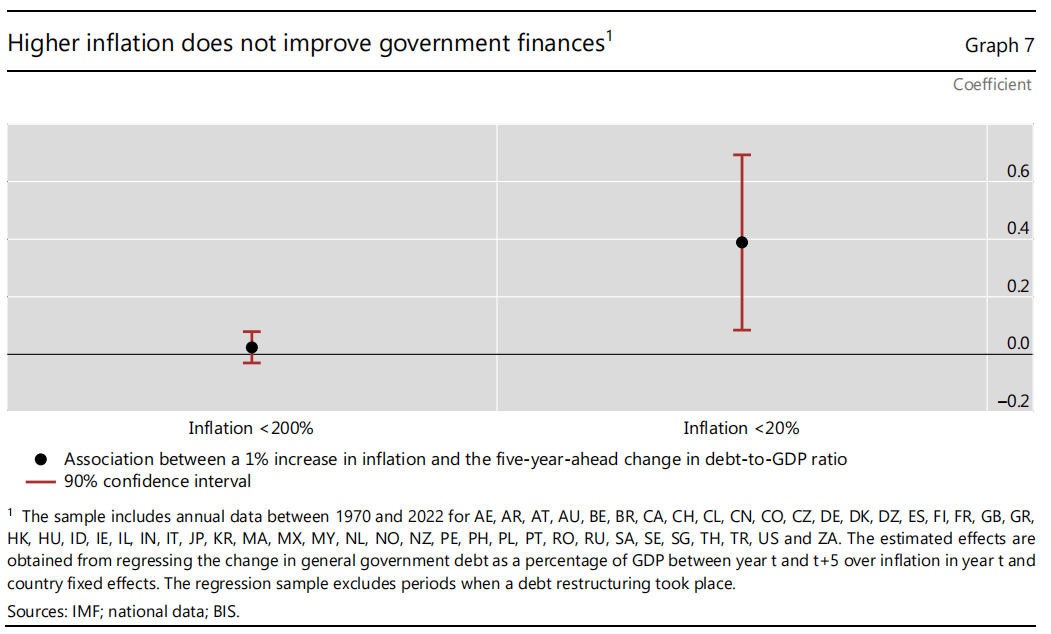

Let me stress that the recent inflation flare-up has cut debt-to-GDP ratios only temporarily. Historical evidence indicates that, in both AEs and EMEs, higher inflation has, if anything, ushered in higher, not lower, debt-to-GDP ratios in the following years (Graph 7). The impact is hardly different from zero even at high inflation rates (left-hand dot and whisker).

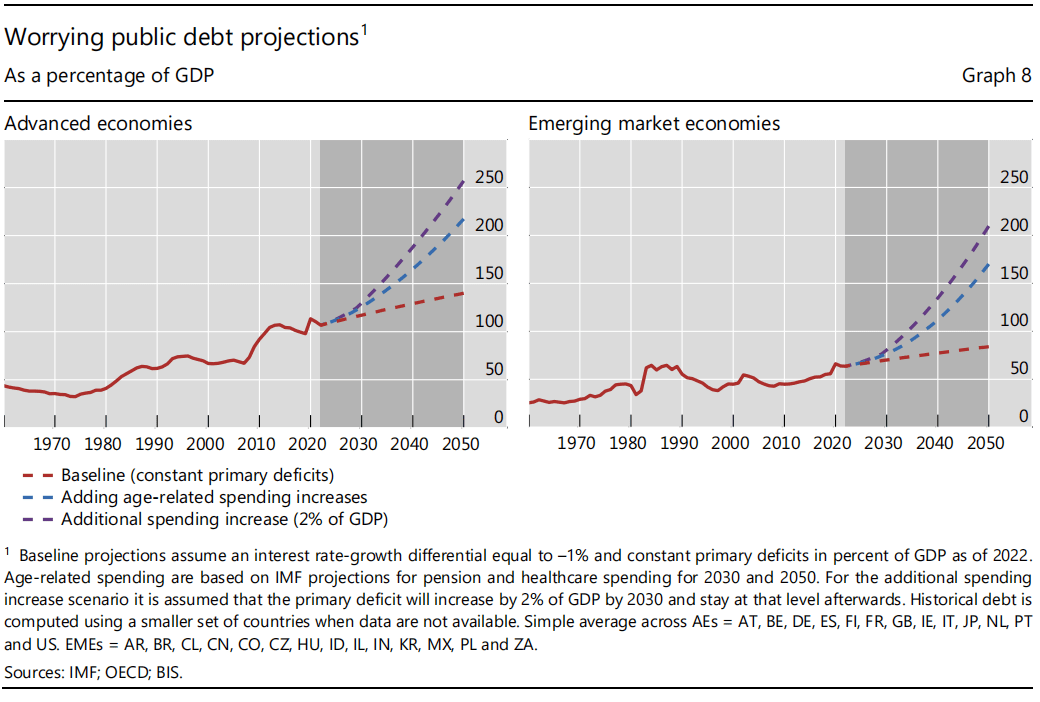

Stylised projections underline the longer-term risk to government finances (Graph 8). Even if interest rates stay below growth rates, absent consolidation, debt-to-GDP ratios are set to climb in the long term from their current historical peaks. The increase would be substantially larger if one factored in the impact of ageing populations as well as those of the green transition and higher defence spending linked to possible geopolitical tensions.

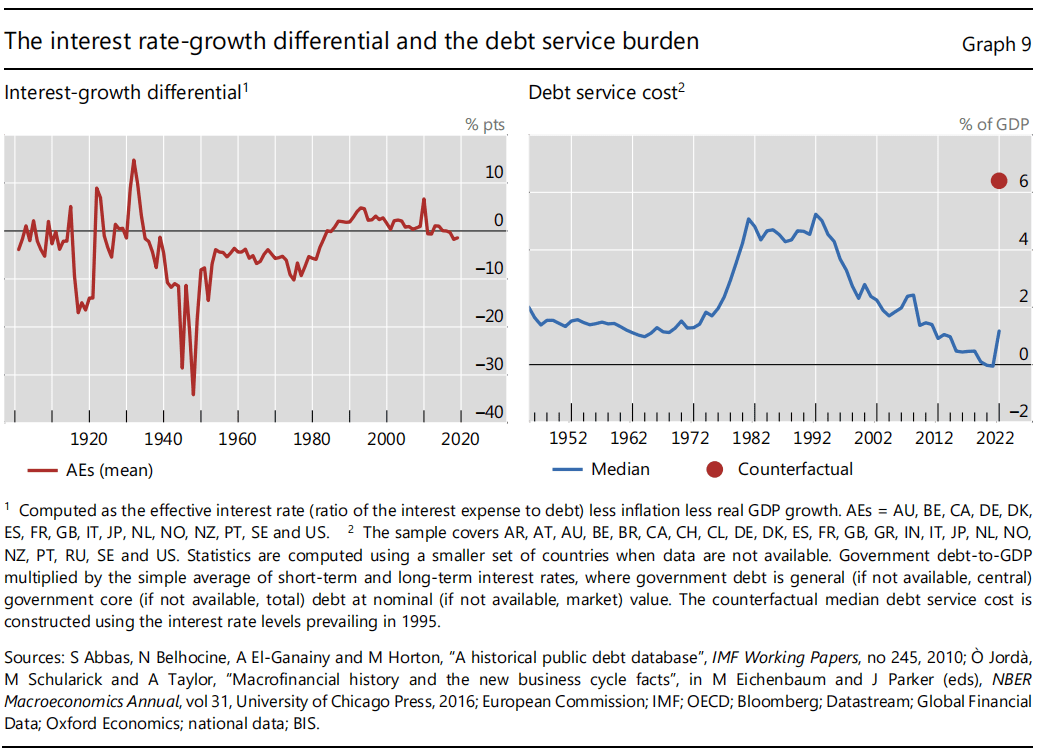

Should interest rates exceed growth rates again, the self-reinforcing dynamics would be much stronger. Moreover, it is not uncommon for the differential to switch sign (Graph 9, left-hand panel). To get a sense of the possible impact of high debt, if today’s interest rates were as high as those in the mid- 1990s – a typical level – all else equal, debt service burdens would over time exceed their historical peak.

This grim outlook for government debt is quite worrying since it raises serious risks for price and financial stability. Let’s consider each in turn.

Price stability

Fiscal policy can greatly constrain monetary policy in its fight against inflation.

Within a certain range, the constraints are manageable: expansionary fiscal policy increases the required degree of monetary policy tightening only to a limited extent and central bank independence provides sufficient safeguards. But when the credibility of fiscal policy or the creditworthiness of the sovereign are lost, monetary policy can be hamstrung: a tightening would only heighten those concerns and fuel inflation, typically through an uncontrolled exchange rate depreciation – a form of fiscal dominance.

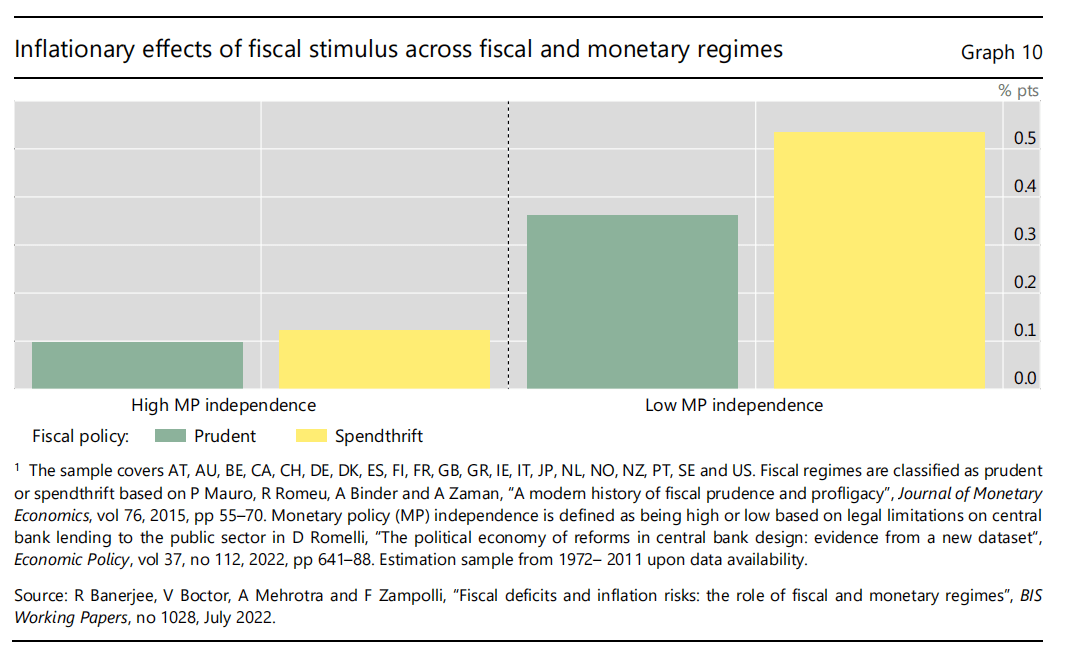

Stylised empirical evidence is consistent with these considerations (Graph 10). The inflationary impact of a fiscal expansion is greater when the fiscal policy regime is less concerned with fiscal sustainability – “spendthrift” rather than “prudent” . Moreover, extreme situations aside, central bank independence is key: inflation is lower regardless of the fiscal policy regime.

Financial stability

Fiscal policy can also constrain monetary policy by triggering or amplifying financial instability.

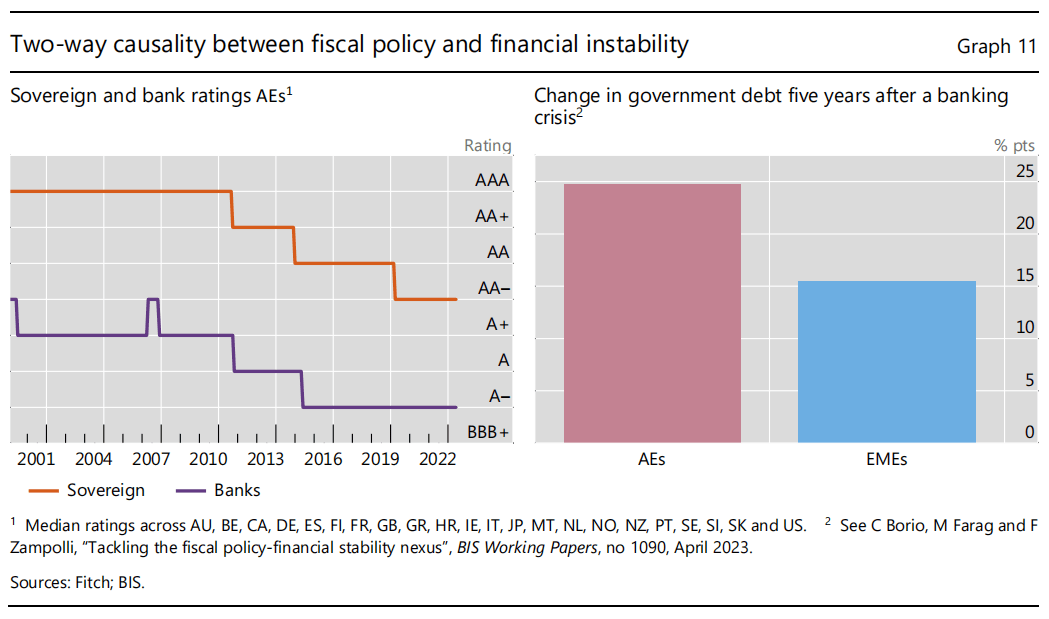

The direction of causality between fiscal policy and financial instability goes both ways. On the one hand, high sovereign indebtedness can cause financial system stress by generating losses for financial institutions, either because of their exposures to sovereign debt or simply by destabilising the economy. This is a key reason why government and bank credit ratings tend to co-move (Graph 11, left-hand panel). On the other hand, financial system stress, regardless of its origin, can cripple fiscal soundness. It can do so directly, as the sovereign may need to backstop the financial system, and, most importantly, indirectly, as the economy tanks. The surge in public sector debt following banking crises is typically well above 10 percentage points of GDP (right-hand panel). This two-way causality can give rise to the infamous sovereign-bank doom loop.

Post-GFC in particular, as sovereign debt has soared, financial institutions have absorbed growing amounts. The corresponding increase in relation to bank capital in both AEs and EMEs has been sizeable (Graph 12, left-hand panel). Given the lengthening of maturities, exposures to interest rate (or duration) risk have also grown substantially (right-hand panel), even where central banks have engaged in large-scale asset purchases. The corresponding potential losses can be quite large.

Indeed, in the year under review, we have already seen how interest rate risk alone can cause stress in the system. Think of the turmoil in UK gilts markets, or of the failure of a number of US banks. The stress would be much more severe should the creditworthiness of some sovereigns be questioned at some point.

Policy

What are the implications of this analysis for policy?

The overriding priority is for monetary and fiscal policy to operate firmly within the region of stability. This requires adjustments to strategies, institutions and mindsets, well beyond monetary and fiscal policies themselves.

For fiscal policy, it is essential to ensure that debt evolves along an unambiguously sustainable path. This is the cornerstone of a well functioning economy and a prerequisite for monetary policy to retain headroom. With regard to strategies, it would be important to pay greater attention to the impact of financial factors on fiscal space, notably to the flattering effect of financial imbalances and to the potential fiscal costs of banking crises. With regard to institutions, it is crucial to give fiscal councils and fiscal rules more bite, possibly through constitutional safeguards.

For monetary policy, the priority is to ensure price stability while paying due attention to financial stability. As regards strategies, once price stability is re-established, it would be desirable to exploit the self-stabilising properties of low-inflation regimes, documented in detail in last year’s Annual Economic Report. This means greater tolerance for moderate, even if persistent, shortfalls of inflation from narrowly defined targets. Greater tolerance would also reduce the incidence of long periods of unusually low interest rates, thereby limiting their side effects, such as the build-up of financial vulnerabilities, the misallocation of resources and the incentive for governments to accumulate debt. As regards institutions, safeguarding central bank independence will be even more important if fiscal positions continue to deteriorate.

Two additional policy areas can substantially enlarge the region of stability.

One is prudential policy, both micro- and macroprudential – the first line of defence against financial instability. An effective prudential framework involves a whole range of elements. Concerning sovereign exposures, more specifically, there is a need to revisit the favourable treatment of sovereign debt in market and credit risk.

Another, badly neglected, area is structural policy. Higher sustainable growth can be achieved only through decisive measures to improve the supply side of the economy. Structural policies have been flagging for too long. They need to be revived with urgency.

Ultimately, however – and let me conclude with this – a change in mindsets is called for. A keener recognition of the limitations of demand management policies is key to overcoming the “growth illusion” described earlier. The concept of the region of stability, hard as it may be to apply in real time, can promote the necessary shift in perspective. The concept is first and foremost a lens through which to look at the world and guide policy. It can help preserve the vital trust that society must have in the state and its decision-making.

编译:周雨平

监制:董熙君

来源|BIS

版面编辑|邸馨逸

责任编辑|李锦璇、蒋旭

总监制|朱霜霜

近期热文

- 海外之声丨BIS总裁:用坚决而现实的政策应对全球挑战

- 海外之声丨BIS总裁:用坚决而现实的政策应对全球挑战

- 海外之声丨BIS金融稳定研究所主席:技术颠覆与气候相关风险的政策应对

- 海外之声 | 印度金融体系与可持续增长

- 海外之声丨IMF副总裁李波:扩大新兴市场和发展中经济体气候融资规模